Rubio’s first foreign tour sets the tone: migration, security, and economic ties

On his first overseas trip as America’s top diplomat, Marco Rubio spent six days hopping across Central America and the Caribbean with a clear brief from the White House: cut illegal migration, hit transnational crime, keep Beijing’s influence in check, and open more doors for trade and investment. The February 1–6 swing took him to Panama, El Salvador, Costa Rica, Guatemala, and the Dominican Republic.

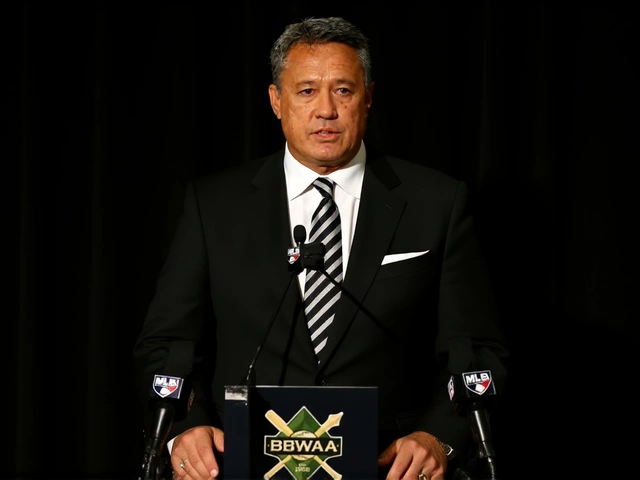

Rubio’s aides framed the tour as proof that the administration’s “America First” approach is about active engagement, not retreat. Department spokeswoman Tammy Bruce said the route reflected both Rubio’s personal interest in the neighborhood—he was a Florida senator and the son of Cuban immigrants—and the urgency of regional issues that spill directly into U.S. domestic debates.

Migration was the through line in every stop. Governments across the isthmus are under pressure as record numbers of people pass through the Darién Gap, a dangerous jungle corridor between Colombia and Panama. That flow pushes north through Costa Rica and Guatemala and eventually reaches the U.S. southern border. Rubio’s meetings focused on disrupting smuggling networks, funding joint border operations, and tightening information-sharing on criminal groups that profit from the routes.

Security talks leaned on a simple calculation: crime and migration feed each other. In El Salvador, Rubio met President Nayib Bukele to study the country’s steep drop in homicides and the clampdown on MS-13 and other gangs. Bukele’s tactics have made him one of the region’s most popular leaders, though rights groups have criticized mass arrests and prolonged detention. U.S. officials see lessons for tackling cross-border gang activity, including Venezuelan-origin groups like Tren de Aragua, whose cells have been flagged by police in North and South America.

Officials also revisited past asylum and migration arrangements. Rubio’s team discussed El Salvador’s prior Safe Third-style cooperation from the first Trump term, exploring whether updated frameworks could speed asylum processing, expand returns for those without valid claims, and protect vulnerable migrants closer to home. Any reboot would have to navigate court rulings, legislative scrutiny, and capacity limits in partner countries.

Beyond enforcement, the pitch included economics. Rubio promoted nearshoring—bringing manufacturing and services closer to the U.S.—as a way to generate jobs that keep people from leaving in the first place. Business roundtables in San José and Santo Domingo touched on medical devices, textiles, digital services, and clean energy supply chains. The State Department has pushed for faster customs procedures, modern ports, and reliable power as baseline conditions for U.S. and regional investors.

Guatemala, now a key partner for U.S. agricultural trade and labor mobility programs, featured discussions on seasonal work visas and anti-corruption support for prosecutors and customs agencies. In Costa Rica, known for political stability and green energy, the focus turned to cybersecurity, incentives for mid-sized manufacturers, and training partnerships to align local skills with U.S. supply-chain needs.

Canal politics, China’s footprint, and the region’s balancing act

Panama was the most sensitive stop. President Trump has repeatedly railed about the Panama Canal, accusing Panama of walking back understandings from the Carter era and criticizing Chinese involvement near the waterway. Panamanian officials reject those claims, stressing that the Panama Canal Authority, a Panamanian entity, runs the canal. Chinese-affiliated firms do operate port terminals and logistics sites, but not the canal itself. The political stake for Washington is clear: the canal is a chokepoint for global trade and a symbol of U.S. strategic reach in the hemisphere.

Rubio’s meetings in Panama City centered on two fronts—migration through the Darién and the canal’s broader security environment. U.S. officials discussed joint patrols, screening of smuggling networks, and technology to track movements along jungle routes. They also talked maritime security, port vetting, and foreign investment reviews around critical infrastructure. The message was that the U.S. wants to be a larger partner in both border management and economic development, not just a critic from afar.

China was a consistent subtext throughout the tour. Several countries on Rubio’s route have switched diplomatic recognition from Taipei to Beijing in the past 15 years, while Guatemala still recognizes Taiwan. Washington’s concern isn’t only flags and embassies; it’s dependence—on loans, contractors, core networks, and ports. Rubio pressed for open procurement, screening of high-risk vendors, and diversification of financing so countries aren’t locked into one pipeline for telecom gear or public-works projects.

In El Salvador and the Dominican Republic, U.S. officials highlighted the risks of opaque infrastructure bids and the need for secure 5G and cloud services. They touted U.S.-backed development finance as a counterweight to state-directed lending. Costa Rica’s role as a tech and services hub came up in conversations about digital rules, data protection, and regional cyber incident response.

Security cooperation got a detailed airing in San Salvador. U.S. law enforcement agencies have long targeted MS-13 leaders with federal indictments and sanctions. Rubio’s delegation examined how joint task forces could cut off gang revenues, track cross-border recruitment, and speed extraditions. They also looked at prisons and rehabilitation programs—areas where El Salvador’s hardline approach has sparked debate—but which U.S. officials say must be part of a durable plan to keep gangs from regrouping.

The Dominican Republic meetings shifted to ports, aviation security, and narcotics routes. The Caribbean is a key corridor for cocaine shipments heading to North America and Europe. Dominican officials have invested in scanners and maritime patrols, but they want more training and intelligence feeds. Rubio pushed for regional fusion centers and better sharing of shipping data, so interdictions are based on real-time risk profiles rather than random inspections.

The migration-security-economy triangle also featured in talks about labor mobility. Officials explored expanding orderly pathways—like seasonal work visas and private sponsorship—while tightening enforcement against smugglers. The aim is to increase legal routes that relieve pressure at the border without signaling an open door to unlawful crossings.

Rubio’s team tried to knit these threads into a single plan: more joint operations, more vetted investment, and more jobs. That means follow-up. Working groups on migration and law enforcement are expected to meet in the coming weeks, with proposals on shared databases, vetted units, and targeted development funds. Business councils from the five countries will be asked to lay out bottlenecks—energy reliability, customs delays, and workforce skills—where U.S. help could unlock private capital.

The politics will be bumpy. Panama wants respect for its sovereignty over the canal even as it welcomes U.S. help against smuggling. El Salvador seeks recognition for its security gains but faces pressure over due process and accountability. Guatemala balances U.S. ties with local political frictions. Costa Rica wants investment without the baggage of great-power rivalry. The Dominican Republic is eager for trade and tourism while guarding against being a smuggling hub.

Rubio’s bet is that a tighter web of practical cooperation—on borders, ports, and factories—can cool migration pressures and curb criminal networks while making the region more resilient to outside leverage. Whether that holds will hinge on money, political will, and how quickly the promises from this first trip turn into working projects on the ground.