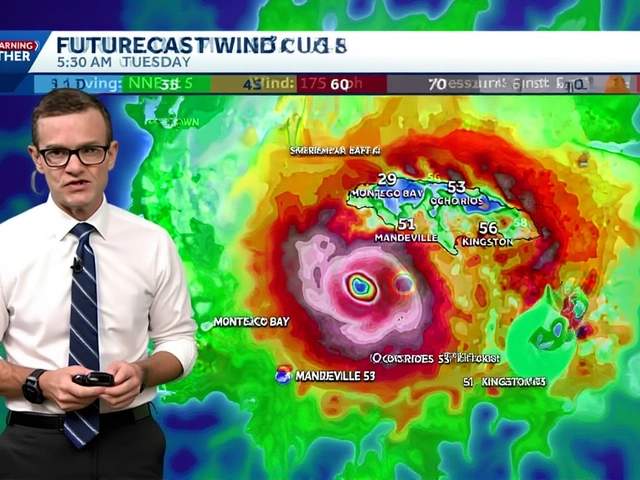

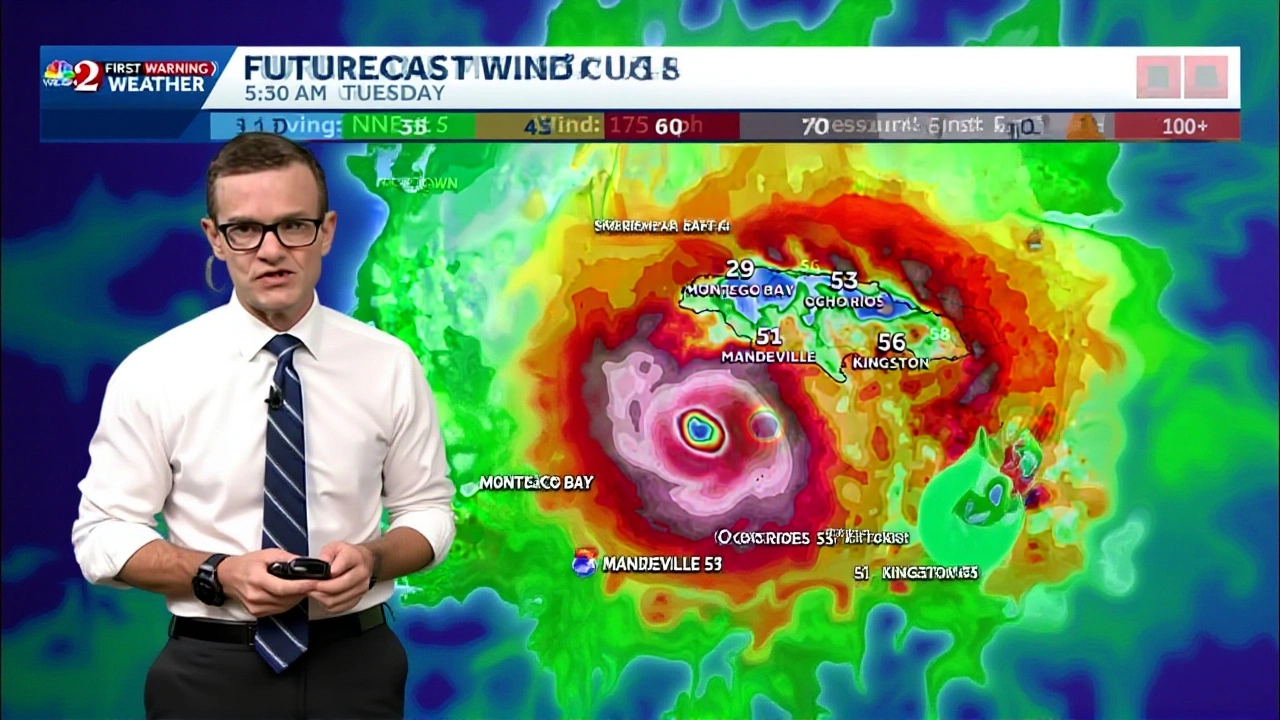

When Hurricane Melissa slammed into Jamaica on Tuesday, October 28, 2025, it didn’t just break records—it shattered them. With wind gusts topping 186 miles per hour, the storm made landfall as a Category 5 hurricane, the strongest classification possible, turning neighborhoods in Kingston into rivers of mud and debris. The United Nations meteorological team called it “the worst storm to hit the Caribbean island this century,” a chilling label that echoed through emergency shelters and ruined homes alike. What made this disaster even more alarming wasn’t just the wind—it was how few people had been moved to safety. While Cuba evacuated over 400,000 residents, Jamaica’s official count was just 6,000. And that’s not a typo.

Landfall in Kingston: A City Under Siege

By midday UTC, Hurricane Melissa had already ripped through Jamaica’s southeastern coast, with downtown Kingston—the capital and economic heart of the island—bearing the brunt. Satellite images showed the city’s skyline vanishing under a churning wall of clouds, while live feeds from Reuters captured roofs flying off buildings like paper kites. Power lines snapped, sending sparks arcing across flooded streets. The storm surge, estimated at 20 feet in some coastal parishes, swallowed entire communities near Portmore and St. Andrew. Emergency crews couldn’t reach many areas for hours. One resident, speaking from a rooftop in Liguanea, told reporters: “We heard the wind scream like a freight train. Then the water came. No warning. No time.”

Evacuation Gap: Why Jamaica’s Response Fell Short

The numbers tell a disturbing story. Cuba, with its centralized civil defense system, evacuated 400,000+ people from Holguín and Guantánamo provinces alone. Meanwhile, Jamaica, despite being hit first and hardest, reported only 6,000 evacuees. Why? The answer lies in infrastructure, resources, and decades of underinvestment. Jamaica’s emergency management agency, Jamaica Disaster Management Agency (JDMA), lacks the transport capacity, shelters, and communication networks to move large populations quickly. Many rural residents don’t own cars. Public buses were already overwhelmed. And in some parishes, officials didn’t even have working radios. “We told people to leave,” said a JDMA official on condition of anonymity. “But when your roads are washed out and your only bus is stuck in the mud, what are they supposed to do?”

Climate Change: The Silent Co-Pilot

As Hurricane Melissa pushed toward Cuba, Carl Shrek, a meteorological analyst who spoke during an NBC News broadcast from Havana, delivered a blunt assessment: “Climate is warming, it is producing more fuel for the storms, also getting wetter with heavier rainfall associated with them. And as the sea levels rise, you're having more storm surge as well.” His words weren’t just commentary—they were a warning backed by science. Sea surface temperatures in the Caribbean this year were 2.3°C above the 30-year average. That’s not a small bump. It’s the equivalent of pouring gasoline on a fire. Hurricane Katrina in 2005 peaked at 175 mph over water. Melissa hit land at 186 mph. And it wasn’t even at its absolute peak. “We’ve been saying this for years,” Shrek added. “But now the math is screaming.”

Cuba Prepares: A Model of Efficiency

By late afternoon UTC, Hurricane Melissa had crossed Jamaica and was barreling toward Cuba as a still-dangerous Category 4 storm. But here, the response was starkly different. The Cuban government, through its National Civil Defense headquartered in Havana, had already activated its nationwide evacuation protocol. Schools, community centers, and even military barracks were converted into shelters. Volunteers knocked on every door. Medical teams were deployed with portable oxygen and insulin supplies. “The farther east you go in Cuba, the more worried people are,” reported Ed Agustin, an NBC News correspondent filing from Havana. “But they’re also better prepared.” The contrast with Jamaica was jarring—and heartbreaking.

What’s Next: Storm’s Path and Global Implications

By late October 28, 2025, Hurricane Melissa was moving northwest, expected to cross eastern Cuba and possibly enter the Gulf of Mexico. No official forecast yet confirmed its next landfall, but meteorologists warned it could re-intensify over warm waters. The real question isn’t just where it goes—it’s why storms like this are becoming the norm. Since 2001, Jamaica has seen 17 major hurricanes. Five of them occurred in the last decade. And each one costs more than the last. The World Bank estimates climate-related disasters have cost Caribbean nations over $2.3 billion since 2020. Jamaica alone lost 12% of its GDP to Hurricane Gilbert in 1988. Now, with Melissa, the toll may be worse.

Historical Context: A Pattern of Vulnerability

It’s easy to call Hurricane Melissa unprecedented. But it’s not. It’s the latest chapter in a decades-long story of neglect. After Hurricane Ivan in 2004, Jamaica pledged to rebuild coastal defenses. Only 30% of those projects were completed. Power grids? Still mostly analog. Emergency sirens? Out of service in 40% of parishes. And while Cuba has invested in community-based disaster training since the 1960s, Jamaica’s system remains top-down and underfunded. “We’re not surprised,” said Dr. Lisa Mendez, a climate resilience expert at the University of the West Indies. “We’ve been screaming into the wind for years. Now the wind is screaming back.”

Frequently Asked Questions

Why did Cuba evacuate so many more people than Jamaica?

Cuba has a decades-old, highly organized civil defense system that trains volunteers in every neighborhood and conducts regular disaster drills. Jamaica’s system, by contrast, is underfunded, lacks transport, and relies heavily on centralized command. Cuba evacuated 400,000+ people; Jamaica only 6,000—despite being hit first by a stronger storm. The difference isn’t just resources—it’s culture and continuity of planning.

How does Hurricane Melissa compare to Hurricane Katrina?

At landfall, Hurricane Melissa had wind gusts of 186 mph, surpassing Katrina’s peak of 175 mph over water and its 127 mph landfall in Louisiana. Katrina caused 1,392 deaths and $125 billion in damage. Melissa’s impact on Jamaica—though less populated—was more intense per square mile. Experts say Melissa’s rainfall and storm surge were also higher due to warmer oceans and rising sea levels.

What role does climate change play in storms like Melissa?

Climate expert Carl Shrek identified three key factors: warmer ocean temperatures provide more energy (“fuel”), increased moisture leads to heavier rainfall, and rising sea levels amplify storm surges. Sea surface temps in the Caribbean this year were 2.3°C above average—enough to turn a strong storm into a catastrophic one. Studies show Category 4 and 5 hurricanes have doubled in frequency since the 1980s.

What’s the immediate humanitarian need in Jamaica?

Clean water, medical aid, and temporary shelter are urgent. Over 80% of Kingston’s power grid is down. Hospitals are operating on generators. The Red Cross reports 12,000 homes destroyed and 50,000 displaced. With roads blocked and airports damaged, international aid is delayed. Local NGOs say they need heavy-duty pumps, water purification units, and mobile clinics immediately.

Will Jamaica rebuild stronger this time?

That’s uncertain. Past reconstruction efforts after hurricanes Ivan and Dean stalled due to corruption, funding gaps, and political turnover. This time, international pressure is mounting. The UN and World Bank have pledged emergency funds, but long-term resilience—like elevated housing, storm-resistant grids, and coastal buffers—requires sustained investment. Without political will, Jamaica risks repeating the same cycle: disaster, recovery, neglect, repeat.

What should other Caribbean nations do to prepare?

They should adopt Cuba’s community-based model: train local volunteers, stockpile supplies in every parish, and integrate disaster drills into school curricula. They must also invest in early-warning systems with SMS alerts and radio backups. And crucially, they need to stop treating climate adaptation as a “future cost”—it’s a survival expense. The next storm won’t wait.